‘Rabbit brained louts’ is what the Daily Express called ‘Young Oxford’; the Oxford Union debating society students who in February 1933 voted by a large majority of 122 that ‘this house will in no circumstances fight for its King and Country’.

Sparked by a bogus letter to the Daily Express, the right-wing papers were spitting fire and fury within days. They declared the vote ‘an outrage on the memory of those who gave their lives in the Great War’. Retired colonels, ex-Oxford men and Conservative MPs all condemned the students in no uncertain terms as ‘aliens and perverts’, ‘woozy-minded communists’ and ‘sexual indeterminates’.

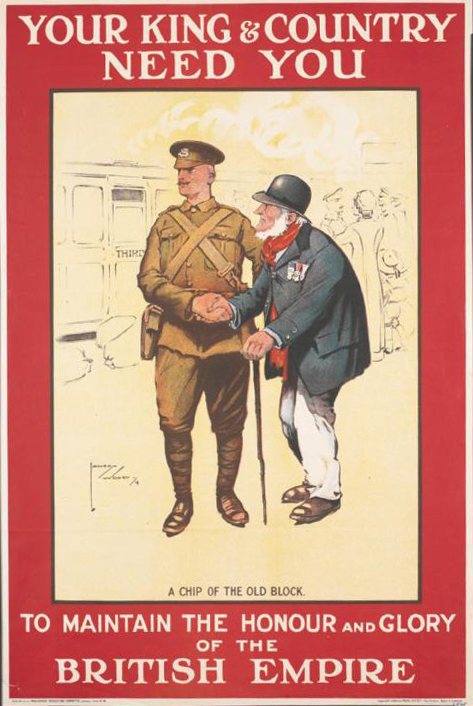

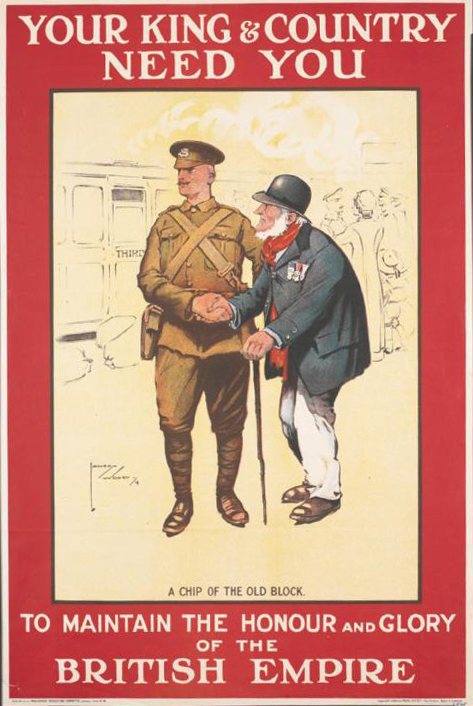

So was this mass pacifism? The students were rejecting what they knew of Lord Kitchener’s famous recruiting slogan in 1915 – ‘your country needs you!’ By the 1920s, the public was questioning what the war had actually achieved. At the time of the debate, the early 1930s, the public backlash against the arms trade – popularly considered to be a cause of the war – had been growing for a decade.

Revulsion against the arms trade combined with a growing horror of the next war. Stories were circulating in the press about the likelihood of chemical warfare should another conflict erupt, with letters appearing even in conventional provincial newspapers like the Oxford Mail. The student generation was haunted by the memory of mustard gas. A stink bomb set off in the Oxford debate and the cries of ‘poison gas!’ was all very funny, but the terror that lay behind it was deadly serious. These students knew what their fathers had suffered from the new technology of warfare: tanks, massive artillery shells, flame throwers, gas. They would have seen what these weapons had done to human bodies and minds first-hand.

And they would have been aware of attempts to disarm and stop the next war, by the League of Nations and numerous local organisations. Banning the arms trade was supported by a majority of British public opinion, as shown by the Peace Ballot a year after the Oxford Union debate. In this enormous poll organised by the League of Nations Union, 90 percent of almost 40 percent of the population voted to prohibit private armaments production by international agreement.

The King and Country debate is a remarkable symbol of anti-war feeling in the early 1930s. At that time most people had direct and recent personal experience of the enormous human cost of the war. Many considered the arms trade to have fuelled the conflict, and profited from the war. Will it take another war for us to care enough to press for disarmament as the public did in the 1930s?