Henry Boddington explores the parallels between the slave trade and the arms trade and explains why ending the arms trade should be a priority for today’s world.

In 1769 the slave, James Somersett was brought to England. He was the property of Charles Steuart a customs officer from Boston Massachusetts, then a British colony in North America. Somersett ran away in 1771 but was re-captured and imprisoned upon a ship bound for the British colony of Jamaica. However, people claiming to be Somersett’s godparents made an application before the Court of King’s Bench for a writ of habeas corpus, and the captain of the ship was ordered to produce Somersett before the Court of King’s Bench, which would determine whether his imprisonment was legal.

The Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, Lord Mansfield, presided over the case that began in February 1772. The case attracted much attention from the press, with activists and industrialists making donations to fund lawyers for both sides of the argument.

On behalf of Somersett it was argued that while colonial laws might permit slavery, neither the common law of England nor any law made by Parliament recognised the existence of slavery, and slavery was therefore illegal. Moreover, English contract law did not allow for any person to enslave himself, nor could any contract be binding without the person’s consent. The lawyers for Charles Steuart argued that property was paramount and that it would be dangerous to free all the black people in England.

Lord Mansfield’s judgement

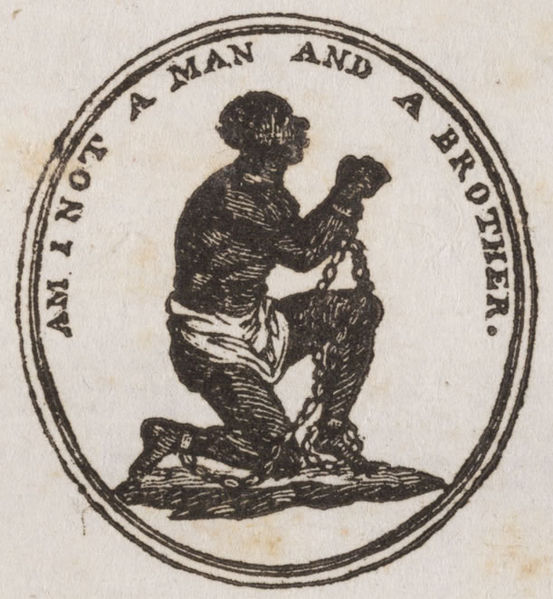

It took Lord Mansfield over a month to reach the judgement that Somersett be set free as there was no common law that could permit the forcible removal of slaves from England against their own will. While the slave trade continued throughout the British Empire until the Slavery Abolition act of 1833, the Somersett case was the launch pad for the emancipation of slaves throughout the British Empire and subsequently the world.

The slave merchants who funded Steuart’s defence were not at all anxious about the fate of James Somersett but were concerned about how abolition might affect their overseas interests. A substantial proportion of the British Empires economy was bound up in the slave trade. Slaves were captured and traded in Western Africa for gold and goods and then shipped off to the colonies to work on plantations. The harvest was sent back to England where there was a great demand, giving rise to a roaring trade that called for more ships, whips and leg irons to be built to transport more slaves to the colonies.

The arms trade – today’s slave trade

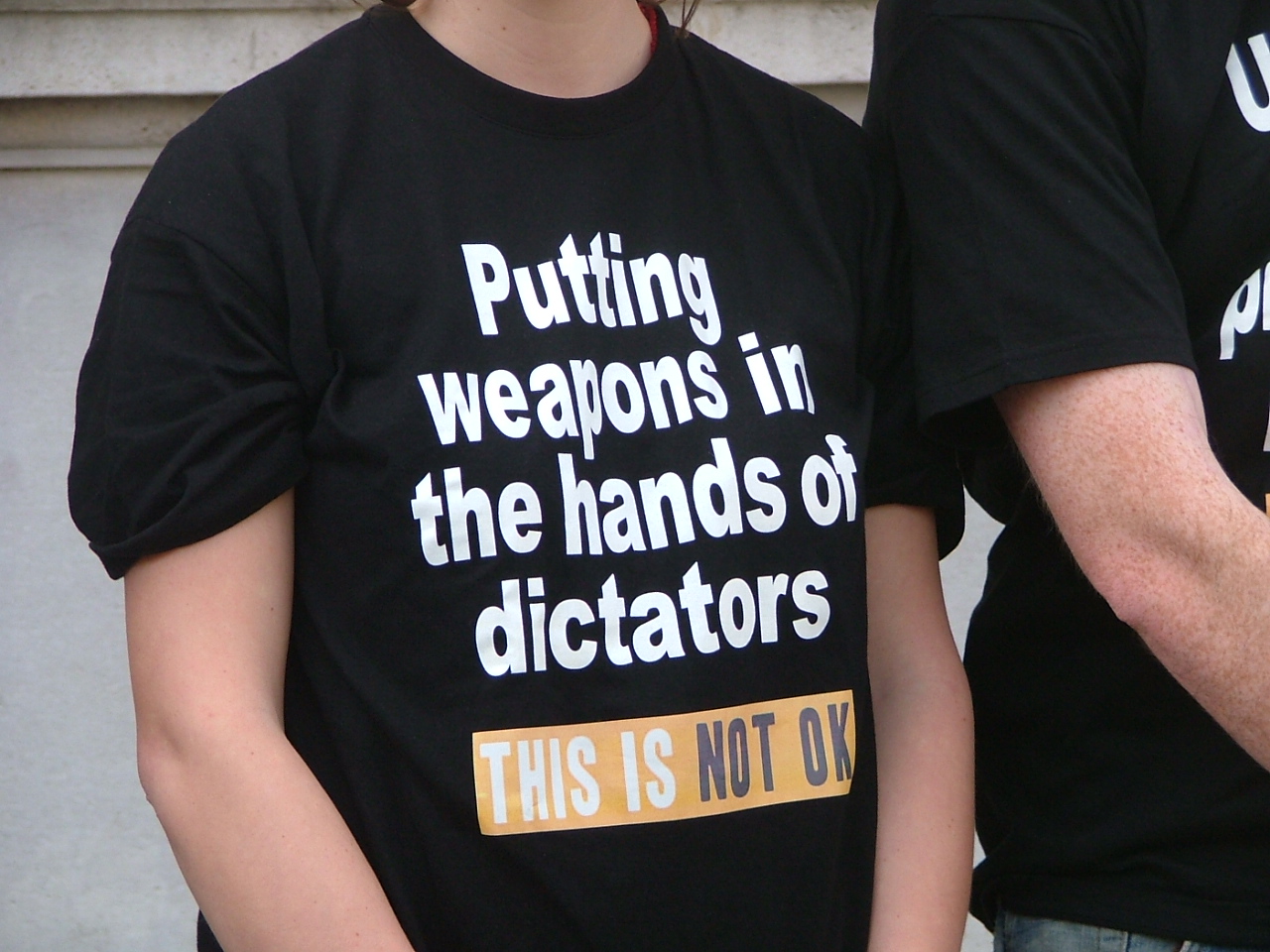

Today we are posed with a similar moral conundrum. For decades we have manufactured and sold weapons to odious regimes and dictators around the world. We have watched our leaders cosy up to criminals and murderers to sell them the tools of oppression and then later condemn them for their transgressions.

There is apparently a multitude of safeguards and laws ensuring that the weapons sold will not be used for oppression, yet as we are seeing today with Gaddafi in Libya and other countries in North Africa and the Middle East, we have no control over how the weapons are used once in the regime’s possession.

Justifications for the arms trade

The arguments for continuing to manufacture weapons for export are bound like those of perpetuating the slave trade. It is often stated that our economic future depends on the continuing trade providing vital employment while we receive concessions on essential imports like oil. Thus our dependence on this trade merry-go-round is too entrenched to simply stop altogether. Peter Luff MP said in his Defence and Security Industrial & Technology Policy speech in November 2010; “I wish to see a healthy economy because our security and defence are directly tied to it.”

According to Global Security, in 2010 the UK defence industry represented ten percent of UK manufacturing, was number one in Europe and second only to the US globally, employing over 300,000 people and generating over £35 billion per year to the UK economy with exports totalling £5 billion. These figures are disputed by Camapaign Against Arms Trade (CAAT) who assert that the true figure of employment is closer to 210,000 people with only 55,000 involved in arms exports.

Parallels between slavery and the arms trade

If we look back again at the slave trade, surprisingly it was not waning as the abolition movement gained momentum. In fact, as the abolition movement began, the slave trade was at its most prosperous. The first recorded Africans enslaved in America were in 1502 with the peak years of the Atlantic trade between 1690-1807 when some six million Africans were transported to the Americas with almost half of them in British or British-North American ships.

Today we look back on the slave trade as a shameful and indefensible stain on our past. However, to capture human beings, imprison them and ship them off to some recess in the far corner of the world to be worked to death was once not only common practice, but commonly accepted as well.

Armaments: a dead-end street

Currently today we seem to have made peace with the fact that death and oppression is an unfortunate by-product of the weapons export business. And why? Because we are fed the lie that exports of British made weapons are good for our economy, UK based employment and trade. Yet the opposite is the case.

Dean Baker the co-director of the Centre for Economic and Policy Research in his article The Economic Impact of the Iraq War and Higher Military Spending states: “Military spending drains resources from the productive economy. It will typically lead to slower economic growth, less investment, higher trade deficits and fewer jobs.” According to figures from CAAT, subsidising the arms manufacturers in the UK costs the taxpayer’s £700 million a year through helping with marketing, financing, and research and development.

Money spent in armaments is a dead-end street. There is a very limited rationale behind stating that it is good for our economy to spend so much money on a product that is absolutely useless. Just think of the very positive benefits that annually could be done with £700 million if it were being spent on education, health, or the environment.

The world is thought to have spent, on average, some $1 trillion per annum on armaments over the last 50 years. A bit of it has gone bang, and when it has done so, it has destroyed itself and it has also destroyed something that someone else has spent time creating. Weapons have a very specific function. They don’t create, they are not benevolent or altruistic tools, and more often they oppress rather than liberate.

Employment and the arms trade

What of the people employed in the manufacture of armaments? What would they be doing if they weren’t creating destructive equipment? Surely they don’t have a very limited skill set only for design of destruction? These are quite possibly some the brightest, most industrious engineers on the planet. Is it too far-fetched to see the same people working on products for renewable energy sources? Could our government not offer them subsidies to help us work towards a sustainable, greener future instead?

CAAT reported that “the UK Government had approved the export of goods including tear gas and crowd control ammunition and sniper rifles to Bahrain and Libya.” The arms-promotion unit of the UK government counts Libya as a “priority market”, and says “high-level political interventions” have supported UK weapons sales there. In November 2010, over half of the exhibitors at the Libyan Defence & Security Exhibition (LibDex) were UK companies.

With the oppression of anti-Gaddafi dissidents bordering on genocide in Libya surely this is the right time to hold ourselves accountable for our export of weapons to heinous regimes. Yes, it is a large-scale decision for the government, but it was the growing voices of public dissension that finally turned the tide of opinion in the UK that slavery was not only an economic and political issue but also a moral one.

During the time of the slave trade, one would be able to say without a hint of moral contradiction that men were good slave owners, implying that they looked after their slaves well. Perhaps today we might also be able to talk about people in kind terms who deal in the arms industry. Whatever their involvement, whether it be manufacturing, providing export licences, investing in stock or shares, sales, export or import, the people concerned are part of a human and economic disaster industry.

Acting against the arms trade

Arguably we are living in the most enlightened time in human history. We know and appreciate the infinite value and potential of each human life more than at any other time. The majority, if not everyone in this world, wants to live in peace. The arms trade on the other hand actively promotes the destruction of human life. Putting weapons into the hands of dictators and evil regimes for profits is just as abhorrent as the end result of state oppression and murder.

Whilst we can take little comfort in the fact we were the first Western nation to abolish the slave trade and then actively enforce the abolition of slavery throughout the rest of the world, it was a step in the right direction. Moreover, once the British had set a precedent the rest of the world soon followed suit.

As Robert Pirsig said “The social values are right only if the individual values are right. The place to improve the world is first in ones own heart, head and hands, and then work outwards from there”. We as individuals have the power to demand accountability. With the growing voices of opposition in North Africa and the Middle East rising up against their oppressive regimes, this could be as seminal a time for the moral question of the sale of armaments as the Somersett case was for the abolition of slavery.