Following our successful legal case against arms sales to Saudi Arabia, CAAT recently joined a host of NGOs and campaigning groups in signing this statement by humanrightsact.org.uk:

Judicial review is an indispensable mechanism for individuals to assert those rights and freedoms against the power of the state.

This FAQ will discuss why judicial review is important to CAAT, and why it is important that not just individuals but also organisations can bring a judicial review.

What is judicial review?

Who can get a judicial review?

Why is CAAT concerned about standing?

What is happening now?

Are judicial reviews political?

But the government says they’re political?

Is something wrong here?

Who will be impacted?

What should the government do?

More reading

What is judicial review?

Judicial review is a crucial legal process in many democracies, including the UK. It allows people to challenge decisions made unlawfully by the state. Where the court finds an unlawful decision was made, the court can apply a remedy. Usually it orders the state body to make the decision again, but this time lawfully.

Judicial review helps to prevent the state from doing whatever it likes. It helps to keep the state’s power from being absolute, and ensures that it acts with fairness, justice, and rationality. Judicial review holds the state to its own rules, and provides a path for wrongs to be righted. These are vital characteristics of a healthy democracy.

Without this important check, the state would be a very big bully. The decisions of regulatory bodies, councils, welfare decision-makers, and immigration authorities could not be challenged. Bureaucrats who don’t like a person or group could simply use state power to punish them in a variety of ways, with no fear of recourse.

When there is no recourse, rules that are meant to bind the state become meaningless.

Who can get a judicial review?

If you have ‘standing’, you can ask the court for a judicial review. To have standing, you must be a person or group with sufficient interest. Sometimes people who bring judicial reviews are organisations, due to their expert knowledge.

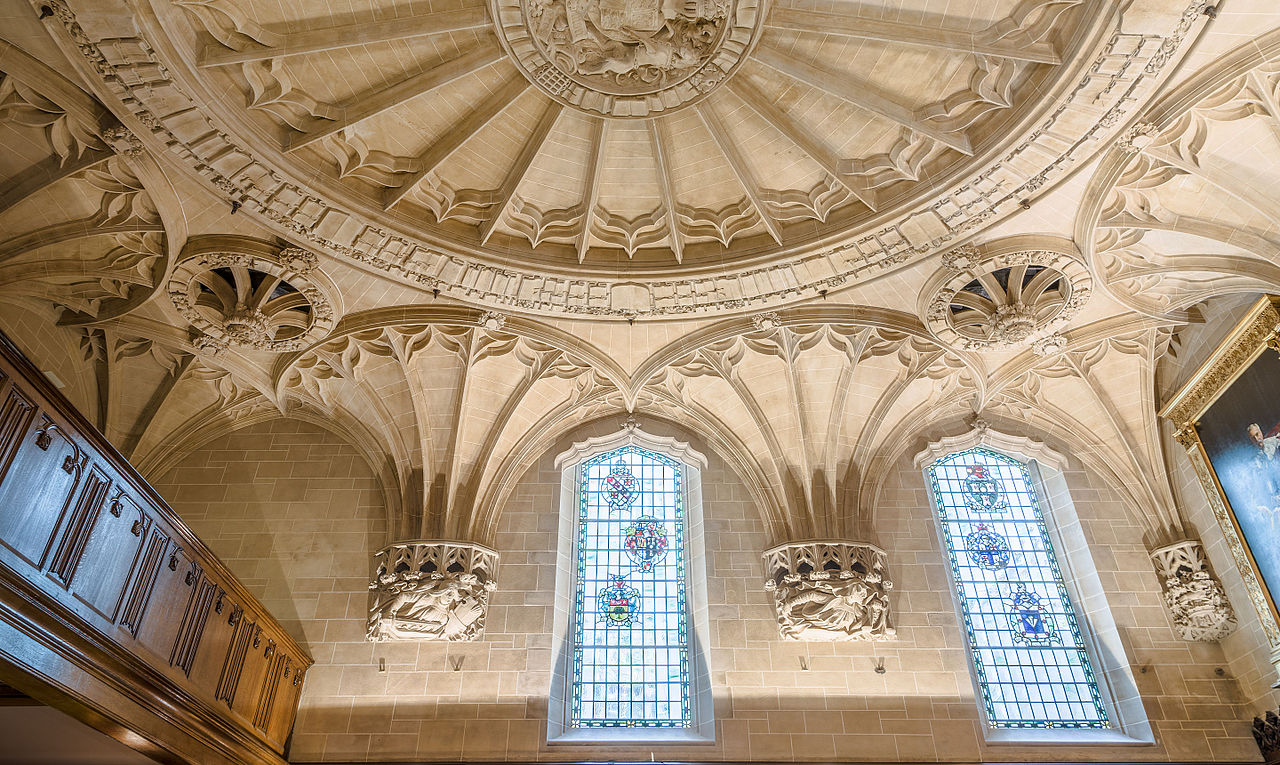

By Anthony M. from Rome, Italy – Flickr, CC BY 2.0

Judicial reviews brought by organisations tend to concern the most widespread and damaging state abuses of power. For example, organisations have won judicial reviews about serious environmental pollution issues, as well as widespread abuse of vulnerable people by the state.

When you ask for a judicial review, you must show you have standing. Without standing, the court cannot listen to you about law-breaking–even if you’re right!

When the government was not following its own arms export rules regarding sales to Saudi Arabia for the ongoing war in Yemen, CAAT had standing to bring a judicial review. CAAT could do this as we obviously have a genuine concern and expertise when it comes to UK arms exports.

Why is CAAT concerned about standing?

Photo by Thomas Martinsen on Unsplash

Standing is one of several areas where judicial reviews can be ‘filtered’ from being heard by the court, through the administrative rules. High costs and short time limits also act as ‘filters’ in England and Wales. These ‘filters’ have been tightened several times recently. The number of judicial reviews that take place each year is falling.

When filters are tightened, the government usually argues that this helps prevent meritless applications for judicial review, and protects the taxpayer from costs.

The danger of tightening filters too much is that it makes it easier for the state to break some categories of rules, because the check on its power is gone. Healthy democracies do not set aside rules without process.

The government sometimes threatens to tighten the rules so organisations cannot have standing. If they succeed, it would effectively set aside arms control rules along with several other categories. This is because in these areas, only organisations are likely to ever have the standing to bring a case in the first place.

What is happening now?

The government is conducting a review of judicial review. The description of the review claims that the purpose is to preserve judicial review whilst ensuring “that it is not abused to conduct politics by another means or to create needless delays.”

The government suffered several major, embarrassing defeats in judicial review cases in recent years. CAAT’s case was one of these. The review is widely believed to be a backlash.

Are judicial reviews political?

Photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash

People cannot bring judicial reviews for political reasons. The court would not hear them.

People bring judicial reviews because they think the state made a decision unlawfully, and those people are concerned experts who want a remedy. The court hears these.

But the government says they’re political?

Lord Sumption, a former Supreme Court justice, says the government doesn’t seem to understand the problem it is trying to address. As a law student, for what it’s worth, I agree.

Concerned experts often do have politics, and this is where the government is confused. Every democratic state does things that some people don’t like. When the issue is serious, like the arms trade is, concerned experts band together and work to change matters. Concerned experts know the rules on their issue. If the rules are being broken, they’re going to notice. Maybe they’re even going to do something about it. That’s what CAAT did. It’s what everyone would do, if only they could.

Is something wrong here?

Yes. Leading law firms and lawyers have criticised the composition of the panel, the structure of the review, and the unnecessary threat it poses to the democratic balance of power.

Who will be impacted?

When judicial review is weakened, the state’s power grows in relation to its people. This particularly affects the most vulnerable people in society, who rely on help from the state and often cannot afford to bring claims in court. Some examples are pensioners, children, people with serious disabilities, and minorities.

What should the government do?

If the UK wishes to retain a healthy democracy, the best way forward is for the government to stop lashing out in this dangerous and short-sighted way, and instead choose to learn from recent mistakes by following its own rules. If it doesn’t like those rules, then instead of breaking them, it should use existing, legitimate processes to change them (paywall). If it doesn’t break rules, experts like CAAT won’t need to alert the court; nobody gets embarrassed; and other awful consequences of rule-breaking stop repeating.

For example, the government has the power to change its arms export rules whenever it likes. Instead it broke them for years, and it lost in court against CAAT. Now it’s going for a repeat.

Instead of attempting to defend its irrational export decisions again, it should stop arming the Saudi coalition. End the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

More reading

- Collection of quotes about the IRAL from leading law firms, former Supreme Court judges, and top lawyers (paywall): “Former top UK judges sound alarm over court review”, Jane Croft, Financial Times, 17 November 2020

- Summary of criticisms of the IRAL: “The defenders of judicial review”, Law Society Gazette, 2 November 2020

- Bindmans’ position on IRAL: “JR review is flawed from square one, says top law firm”, Law Society Gazette, 28 October 2020

- Succinct IRAL submission from the Joint Committee on Human Rights, 20 October 2020

- Dr Mark Elliott’s explanation of standing, written in 2013 (reaction to a previous threat against organisational standing)

- IRAL panel head Lord Edward Faulks QC’s blog, criticising the result of the prorogation case: “The Supreme Court’s prorogation judgement unbalanced our constitution”, ConservativeHome website, 7 February 2020