A corrupt business

Several factors make the arms trade, and especially major arms deals, likely to be corrupt:

- The secrecy surrounding the trade;

- The huge value of individual deals, providing opportunities for enormous bribes for individual decision-makers, even on just a few percent of the deal’s value;

- The technical complexity of major arms deals, making it easy to hide corrupt payments in the deal’s value, and corrupt motivations in the selection process;

- The desperate competition to make big sales by different arms exports;

- The willingness of exporting governments to turn a blind eye to corruption, or even actively support it, to help their arms industry’s make the sale;

- The close connection of the arms trade to top politicians in both buyer and seller countries also opens the way to the use of arms deals and the bribes that go with them for political gain, to fund election campaigns or line the pockets of key allies.

The UK has been involved in a large number of major arms trade corruption cases, many involving BAE Systems, the UK’s largest arms company, but also Rolls Royce, Airbus, and others. The UK government has often failed to take action in such cases, or even actively obstructed them.

Not a victimless crime

Corruption is not victimless. It undermines democratic accountability and drains resources away from health care or education. Projects involving bribes are often over-priced to allow the companies to recoup the money spent on bribes, and these costs can be passed on to the consumer or taxpayer in some form.

When South Africa signed deals worth $5 billion for arms it didn’t need in 1999, it was in the midst of the horrific HIV/AIDS epidemic, yet the government claimed it could not afford life-saving anti-retroviral drugs for its citizens. The arms deals, with arms companies from five European countries, including BAE Systems in the UK, were motivated by at least £300 million worth of bribes paid by the companies to key decision-makers in the South African government.

Opinion has moved strongly in the direction of seeing corruption as a wrong which distorts trade, and in 1997 the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) adopted an Anti-Bribery Convention. In the UK, a clause in the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 made bribing a foreign official a criminal offence from 2002. Dedicated anti-corruption legislation came with the Bribery Act 2010, which came into force in July 2011.

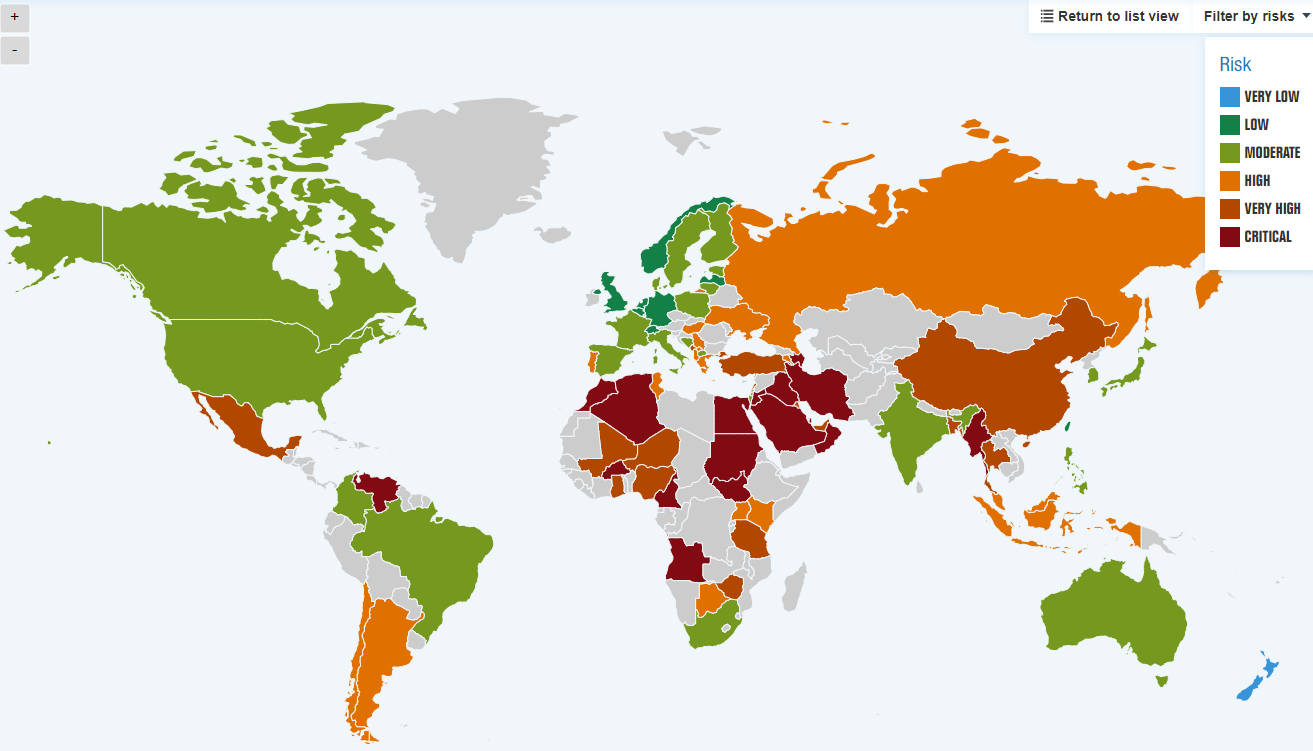

Corruption Tracker

CAAT is proud to be a sponsoring organisation of the Corruption Tracker, a women and youth-led project that seeks to delegitimise and dismantle the arms trade using the lens of corruption. The Corruption Tracker (CT) collates, documents, and exposes information about corruption in the international arms trade, with 62 cases currently documented on their website. CT is also sponsored by the World Peace Foundation and Shadow World Investigations.