The US has been continuously at war in numerous countries around the world since the attacks on the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon carried out by Al Qaeda on 11 September 2001. Initially dubbed a “Global War on Terror”, these wars have come to be seen as “forever wars” – unending conflicts against a shifting series of enemies, mostly non-state armed groups with little or no connection to the original Al Qaeda group, in a futile pursuit of security through bombing, special forces operations. These wars, most prominently the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and the illegal invasion of Iraq in 2003 – in both of which the UK was a key ally – have caused hundreds of thousands of civilian and military deaths, displaced millions of people, and devastated societies and economies across the Middle East and beyond, while costing the US trillions of dollars.

The multi-fronted ‘Global War on Terror’

When terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on 11 September 2001 killed nearly 3,000 people, then-US President George W. Bush declared a ‘Global War on Terror’. Within a week, the US Congress passed, almost unanimously, an Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF), enabling military retaliation by the US. While theoretically directed against Al Qaeda and allied forces, the AUMF was interpreted by successive administrations as allowing military force against any country or group considered by the US to be a threat or acting contrary to its interests. The designation by President Bush of Iran, Iraq, and North Korea as an “Axis of Evil” in January 2002 set the stage for aggressive military action in the years to come.

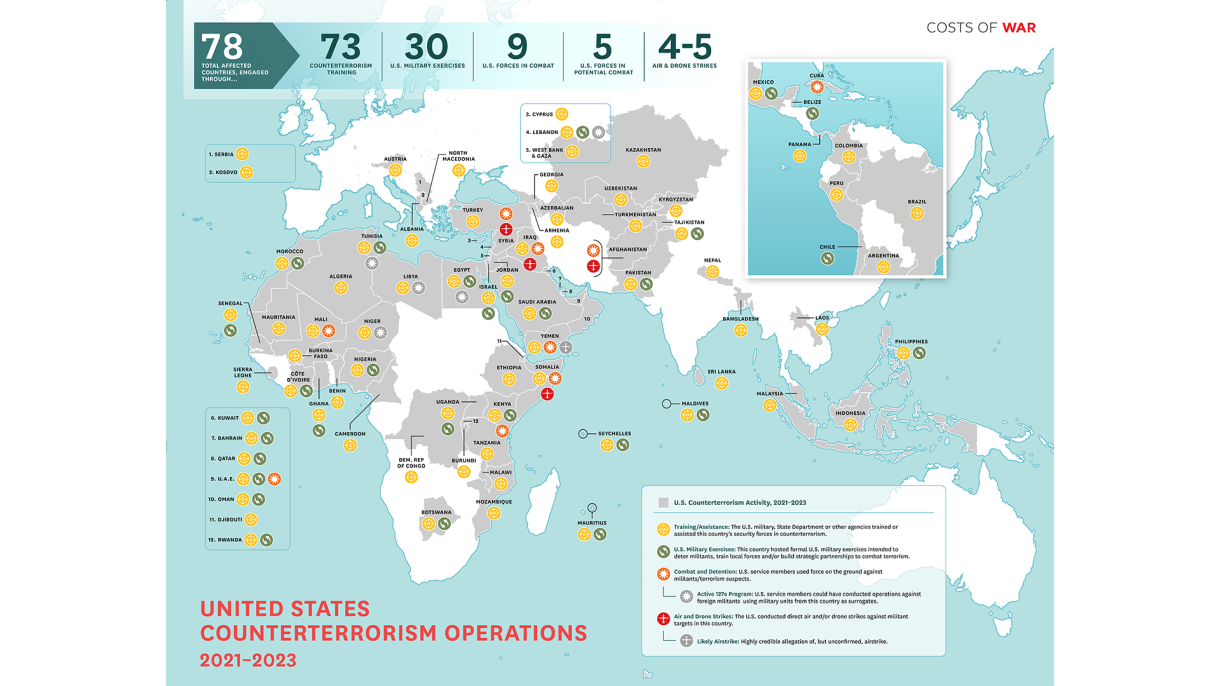

The US-led invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq in 2001 and 2003 respectively – both carried out with the UK as a key partner – were the biggest wars that followed the War on Terror declaration, but far from the only ones. (See map below). In 2010 and the years that followed, investigations uncovered US CIA paramilitary ‘strike forces’ in Afghanistan, Georgia, Iraq, Kenya, the Philippines, Somalia, the tri-border region of South America, Yemen and beyond.

Afghanistan and Iraq

The US and UK launched a bombing campaign to overthrow the Taliban regime in Afghanistan in October 2001, with the stated justification that the Taliban were harbouring Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda, responsible for the 9/11 bombings. What followed was 20 years of intermittent bombing and special forces campaigns in Afghanistan, in neighbouring Pakistan, and particularly along the Afghan-Pakistani border.

Just over 18 months later, in March 2003, the US and a coalition of partners notably the UK invaded Iraq, an act of aggression that was clearly illegal under international law, was based on the false claim that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction, and (by the US) the equally false claim that Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein had collaborated with Al Qaeda in the 9/11 attacks. Hussein was overthrown, and the country quickly descended into factional fighting, while the US engaged in conflict against various Islamist groups, notably Al Qaeda in Iraq; by 2006, Iraqi civilian deaths were peaking at between 1,000 and 3,500 per month. The US began arming Sunni militias to fend off various adversaries, officially withdrawing US troops in 2011. Generalised insecurity contributed to the rise of the Islamic State, which at its height in 2015 controlled 30-40% of both Iraq and Syria.

In both Afghanistan and Iraq, the UK and other coalition members worked closely with the US. Both US and UK troops committed war crimes in both countries, some of the most notorious of which involved torture and sexual abuse of Iraqi detainees at Abu Ghraib prison. The US also carried out the “extraordinarily rendition” of individuals of many nationalities, to abusive indefinite detention at its infamous Guantanamo Bay naval base, which at its height held over 780 individuals, all but 15 of which have been released, most without charge. With the aid of friendly governments, the US maintained an extensive network of black sites where detainees were tortured.

In 2020, during President Trump’s first term, the US and the Taliban signed the Doha accord, which promised a US military withdrawal if the Taliban pledged to prevent Afghanistan from being used as a base for groups acting against American interests. Later that year, the acting US Defense Secretary Christopher C. Miller announced plans to halve the number of troops by mid-January, when President Biden would take office. Biden pledged to end the “relentless war”, and announced the US’ intention to complete its military withdrawal from Afghanistan by 11 September 2021. Coinciding with troop withdrawals, on 15 August 2021, the Taliban rapidly seized the entirety of Afghan territory following the collapse of the Afghan National Security Forces and the fall of the government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, causing mass panic. The last US troops withdrew by 30 August.

The US, recognising in a grand understatement that “many of the challenges that U.S. policymakers sought to address after 2021 persist,” has since quickly deemphasised Afghan security as a policy objective. According to the US Congress, in 2025, the US does not recognize the Taliban or any other entity as the government of Afghanistan and reports there are no U.S. diplomatic or military personnel in the country. The US Congress created a bipartisan Afghanistan War Commission in 2021 to “examine the key strategic, diplomatic, and operational decisions”; its final report is due in August 2026. The US’ Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), created in 2008 to oversee ‘reconstruction’ amidst the fighting, is also expected to finish its mandate in January 2026. As for Iraq, the Obama administration launched Operation Inherent Resolve in 2015 to attempt to counteract Islamic State. By 2017, major combat operations against Islamic State ended, and so in 2024, the administration announced a ‘transition’ – the announcing State Department official wanted to “foot-stomp the fact that is not a withdrawal.”