The Revolving Door

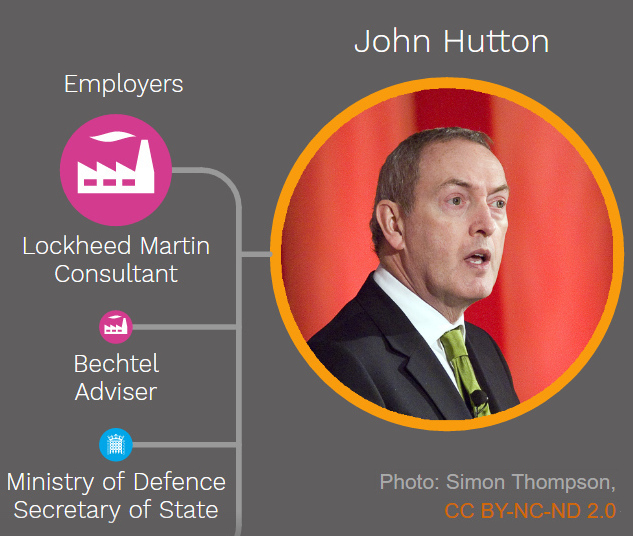

A disturbing number of senior government officials, military staff and ministers have passed through the ‘revolving door’ to join arms and security companies.

This process has helped create the current cosy relationship between the government and the arms trade – with politicians and civil servants often acting in the interests of companies, not the interests of the public.

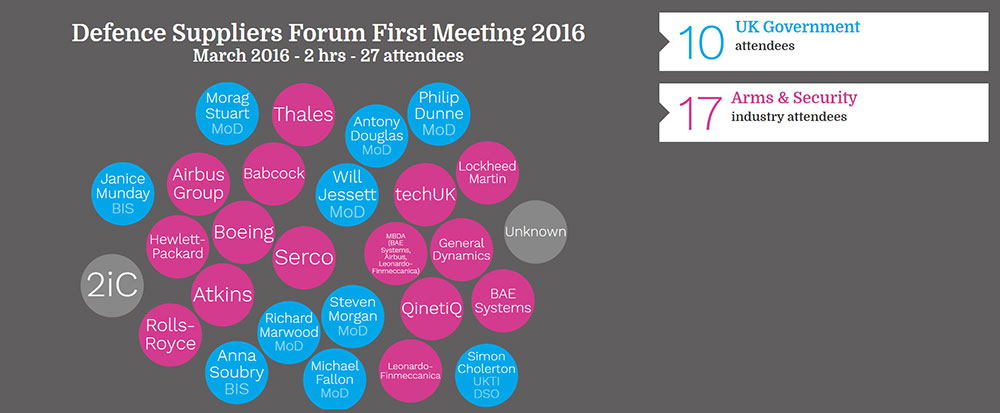

When these ‘revolvers’ leave public service for the arms trade, they take with them extensive contacts and privileged access. As current government decision-makers are willing to meet and listen to former Defence Ministers and ex-Generals, particularly if they used to work with them, this increases the arms trade’s already excessive influence over our government’s actions.

On top of this, there is the risk that government decision-makers will be reluctant to displease arms companies as this could ruin their chances of landing a lucrative arms industry job in the future.

Beyond individual decisions, the traffic from government to the private sector, and vice versa, is part of a process where the public interest becoming conflated with corporate interest, so that it becomes normal to unquestioningly meet, collaborate and decide policy with the arms industry, then take work with it.

All this helps create a sense of “groupthink”, where the assumption that the arms industry is a crucial part of the UK economy, whose well-being advances the good of the nation as a whole, goes unquestioned.