Intensive efforts by the World Food Programme, UN OCHA, and international and Yemeni NGOs are preventing an even worse death toll, but their programs are severely underfunded, with international donor governments falling far short of their promises.

A man-made catastrophe

The starvation in Yemen is an entirely man-made catastrophe, the result of the devastating war in the country, and the strategies and tactics adopted by the parties to the conflict, especially the Saudi-led Coalition.

Some of these strategies suggest the deliberate use of starvation as a weapon of war, which would constitute a war crime.

Displacement of people

4 million people, around 13% of Yemen’s population, are currently displaced, disrupting their livelihoods, sources of income, homes, and communities.

Destruction of economic infrastructure and activity

The war, especially the bombardment by the Saudi-led Coalition, has destroyed factories, roads, bridges, ports, and distribution networks, causing massive bankruptcies and unemployment, while making it much harder to get food and other goods to market.

Production in many areas has been halted by a lack of fuel and supplies, workers have been recruited into armed groups, displaced, injured, and killed.

In 2016, the Saudi-led Coalition gained effective control of the Central Bank of Yemen, which was moved from Houthi-controlled Sana’a to Aden, controlled by the Coalition and its Yemeni allies. It immediately enforced a halt to the payment of government salaries, pensions, and social welfare payments to Houthi controlled areas, drastically impeding the ability of recipients of these payments to buy food.

The Yemeni rial has massively devalued, making imports, on which Yemen is heavily dependent, far more expensive. All this has led to a huge fall in the purchasing power of Yemeni people, making food unaffordable even when it is available.

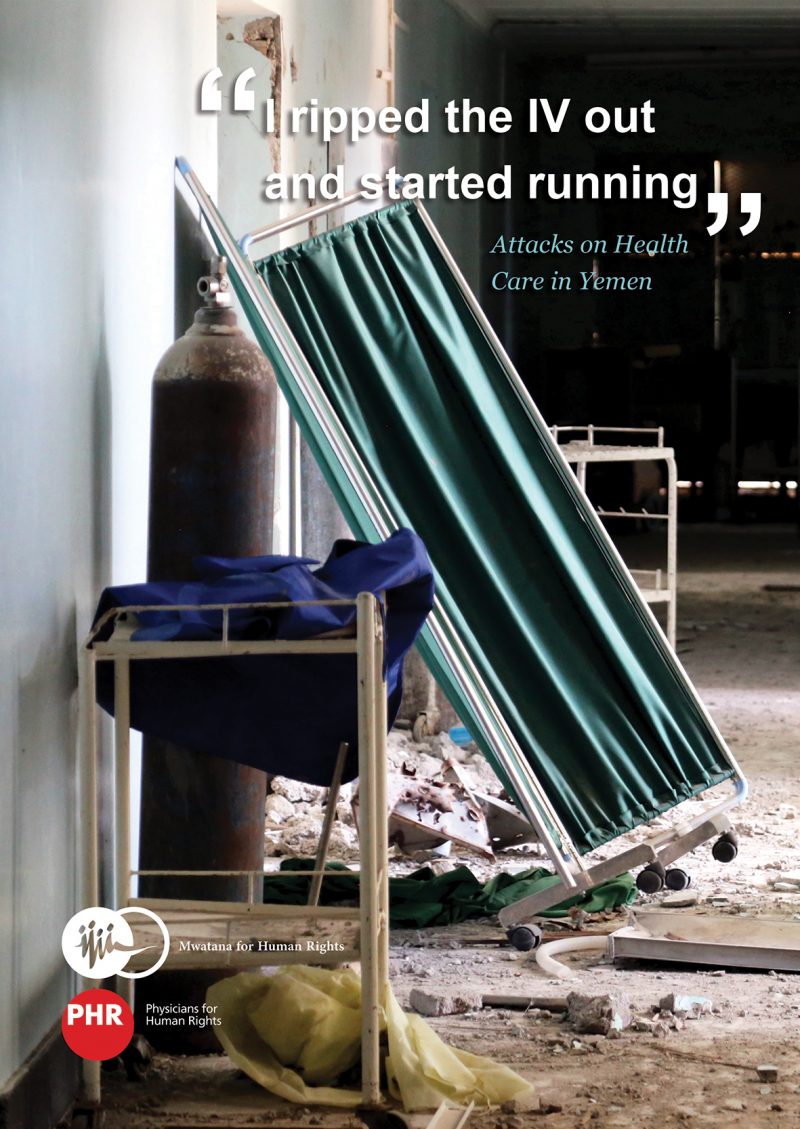

Collapse of the healthcare system

Yemen’s healthcare system has largely collapsed, due to the frequent bombing of hospitals and other health-care facilities, as well as the general displacement and disruption described above.

This has made it much harder to provide proper medical care to those suffering from the effects of the conflict, and has worsened the spread of disease, to which those suffering from malnutrition are so vulnerable. At the end of 2021, only 50% of health facilities in Yemen were fully functional.

In April 2017, the world’s worst cholera epidemic broke out in Yemen, with an estimated 2 million suspected cases up to August 2019, and 3,500 associated deaths. The epidemic saw a resurgence in 2019. The Saudi-led blockade has also made it far harder for hospitals and clinics to obtain medicines and supplies.

This deadly cholera outbreak is the direct consequence of two years of heavy conflict.

Statement from UNICEF and WHO June 2017

“Collapsing health, water and sanitation systems have cut off 14.5 million people from regular access to clean water and sanitation, increasing the ability of the disease to spread. Rising rates of malnutrition have weakened children’s health and made them more vulnerable to disease. An estimated 30,000 dedicated local health workers who play the largest role in ending this outbreak have not been paid their salaries for nearly 10 months. We urge all authorities inside the country to pay these salaries and, above all, we call on all parties to end this devastating conflict.”

The Saudi coalition blockade

The Saudi-led Coalition controls Yemeni airspace, and has closed Sana’a International Airport to commercial flights since August 2016. As many as 32,000 sick Yemenis may have died by August 2019 due to being unable to leave the country to receive treatment overseas, according to the Norwegian Refugee Council, while hospitals have been unable to obtain supplies, or faced much higher prices.

The Coalition has also imposed a partial blockade on Yemeni ports under Houthi control, on the pretext of preventing the smuggling of arms to the Houthis. For 16 days in November 2017, the Saudis and their allies imposed a complete blockade on all Yemen’s ports, threatening immediate catastrophe, though they were persuaded to lift this through international pressure.

This blockade has been described by UN human rights experts as constituting collective punishment, a war crime.

Nonetheless, despite the setting up in 2016 of a UN Verification and Inspection Mechanism for Yemen (UNVIM) to inspect incoming vessels for weapons and other illicit goods, Saudi Arabia has insisted on imposing its own additional inspections. Thus, they routinely stop and board vessels, sometimes diverting them to their own ports, and often imposing long delays, sometimes refusing permission to land altogether.

Amnesty International described this policy as placing a stranglehold on Yemen in July 2018, and these practices have continued up to the present day. As a result, while humanitarian supplies are eventually allowed to arrive, the ability of Yemen to import food – the country imported 90% of its food supplies before the war – has been severely reduced.

The Coalition’s military assault on Yemen’s chief port of Al Hudaydah in 2018 also severely impeded food and fuel supplies, and led to the displacement of tens of thousands of people, until the December 2018 Stockholm Agreement led to a ceasefire. The situation with fuel is even worse, as the Coalition has closed the key marine oil terminal of Ras Isa.

Obstruction of humanitarian aid

The Houthi forces, who control the Yemeni capital Sana’a, and most of the north-west of the country are also deeply responsible for the humanitarian crisis. According to a Mwatana report, they have frequently arrested and intimidated humanitarian workers, blocked aid convoys and illegally seized the property of humanitarian organizations and workers. They have also made widespread use of landmines, further impeding humanitarian access.

Armed groups have taken supplies for their own use, or required bribes to allow deliveries through. This has prevented aid from reaching those who need it most. In one World Food Programme survey in food distribution centres in Sana’a in 2019 for example, 60% of intended beneficiaries said they had received no food aid. WFP staff and independent monitors have been blocked from making monitoring visits. As a result of these obstructions, the WPF partially suspended aid deliveries to Houthi-controlled areas in June 2019.

Destroying the means of life

One of the most insidious strategies of the Saudi-led coalition in pursuing their war in Yemen is to destroy the economic and social foundations of society in Houthi-held areas by targeting key infrastructure, civilian factories, and even the very means of sustaining life, by targeting agriculture and food production and distribution.

Once we control them, then we will feed them

Anonymous Saudi Diplomat, from Strategies of the Coalition in the Yemen War by Martha Mundy

Transport infrastructure have been repeatedly targeted, which has increased the difficulty of distributing food and fuel supplies around the country, a key contributing factor to the famine-like conditions in Yemen.

Such attacks on civilian infrastructure, even where there are no direct civilian casualties, are clear violations of International Humanitarian Law.

Perhaps most shocking is the deliberate targeting of agricultural, food and water facilities. A report in 2021 by Mwatana, Starvation Makers, found that the Saudi-led coalition carried out:

…A pattern of repetitive attacks on similar OIS [objects indispensable for survival], e.g. on farms, water facilities and artisanal fishing boats and equipment, and on other types of OIS, including food markets, means of transporting food and water, and food and water storage and production facilities.

Many of the water facilities were attacked multiple times by airstrikes, sometimes after they had been rebuilt or repaired.

A 2018 report by Martha Mundy and World Peace Foundation catalogues the systematic targeting by the Coalition of agricultural land, animals and animal farms, agriculture and irrigation offices, markets, water infrastructure, and transport infrastructure. This has led to a major drop in agricultural production in many areas.

The very small proportion of Yemen’s land area devoted to agriculture – less than 3% &nsash; makes it hard to see such attacks as accidental. Moreover, there are cases where vital facilities such as irrigation works have been repeatedly attacked, again strong evidence of deliberate targeting. In the key port city of Al Huydaydah, food warehouses and distribution centres, a flour mill, and other food production and distribution facilities have been bombed.

Meanwhile, along the Red Sea coast, fishing ports and boats have been frequent targets of attack. Between March 2015 and July 2018, 71 airstrikes targeted fisheries. By the end of 2017, these strikes had destroyed 222 boats and killed 146 fishermen.

These attacks have greatly harmed Yemen’s ability to produce food, at the same time as the partial blockade of Yemen’s ports by Saudi Arabia, restricting food imports, have all contributed to the current humanitarian crisis. Mwatana, international legal NGO Global Rights Compliance, and others, have concluded that both the Saudi-led coalition and the Houthis are guilty of the deliberate use of starvation as a weapon of war – which would constitute a war crime.

One Saudi diplomat, interviewed off the record about the threat of starvation in Yemen, responded: “Once we control them, then we will feed them”.